Impressions from Ioannina: School matters

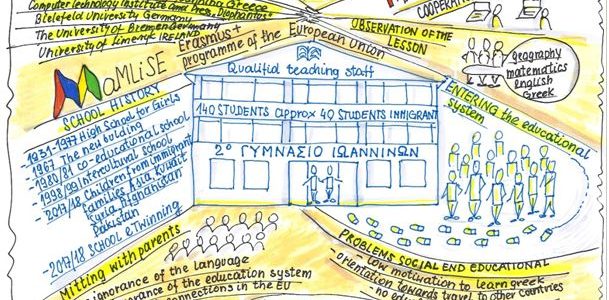

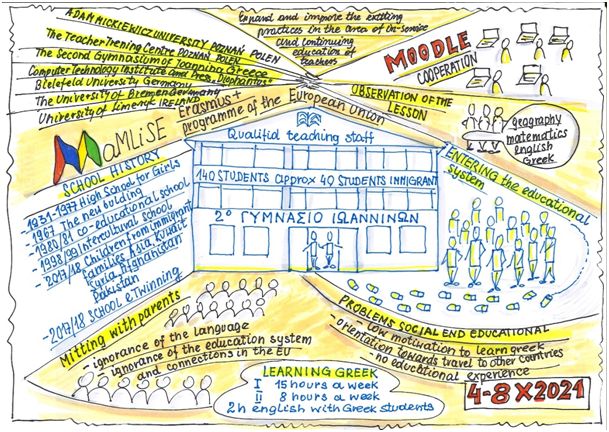

The 2nd Junior High School of Ioannina Intercultural Education is a small school in Greece that is attended by about 140 students, of which more than 30 are migrants from Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Pakistan and Algeria. The school is one of 26 schools in Greece that are called multicultural schools. For a school to be characterized as such, more than 45 percent of the student body need to come from other countries. A considerable number of children from other countries outside of Greece are transferred to these multicultural schools due to a wide array of reasons. Multicultural schools are spread all over Greece and provide education at three levels: primary, middle and secondary school.

Children of migrant backgrounds can also attend regular schools in Greece where they learn Greek in additional courses in the form of additional classes which are delivered in the timeframe of a few hours per week. Children staying in refugee centres can study within their accommodation facilities. Some children stay in Greece without adult guardians/parents. They are then accommodated in special hotels run by NGOs and can receive their education there.

In the multicultural school in Ioannina, which we had the opportunity to visit within the framework of the MaMLiSe* project, pupils with migration experiences are offered a special two-year programme of education (called ‘reception class’). Children enrolled in this learning path in the first year learn 15 hours of targeted Greek language input in the first year. They work with other foreign students in small class sizes in groups for foreigners. In addition, these pupils attend the remaining lessons (English, German, Mathematics, Computer Science, Gym, Home Economics) with students of Greek descent. In the second year of schooling, the Greek lessons are reduced to 7-8 hours per week, but the children with migrant backgrounds have additional lessons in regular classes with local Greek students.

This system of teaching and integration has been in operation at the school for four years, but the 2nd Junior High School of Ioannina has a long-standing experience in teaching multicultural and multilingual classes. For instance, in the 1990s, classes for Greek expatriates were taught here. In 1996, then-Minister of National Education George Papandreou, himself a repatriated Greek, shifted their mission to teach new immigrants, and over the past 25 years, children of migrant backgrounds have continuously attended the school in greater or lesser numbers. The headmaster, who has managed the school for many years, also has experience in teaching and managing this kind of school, as he was the headmaster of a Greek school in Germany.

During the study visit to the school, we had the opportunity to observe a variety of lessons taught by the teachers of Greek, English, Mathematics, Biology, Household Economics and PE. The Greek lessons were conducted in the reception class. These students receive licensed textbooks for this subject which resemble Polish primers for elementary school children. In addition, teachers prepare audio-visual materials, mostly to practice receptive language skills (listening/reading) and the productive language skill of speaking. For children of non-Greek origin, writing appears the most challenging skill to master (due to the need to master the Greek alphabet). Therefore, writing skills are not assessed and required in the first years of schooling.

The Greek language lesson we observed was about the morning routine. Students worked in a computer lab and solved some of the tasks online. The goal of the lesson was to master the vocabulary and structures to formulate statements about morning activities (e.g., getting up, washing up, leaving home, saying goodbye). The students first matched the vocabulary to the pictures and listened to the sounds of everyday activities. Then, they composed sentence structures and talked about their day. Those who were more advanced could also write. During oral presentations, students spoke first in their first language and then in Greek. This approach, the teachers said, is common in the school. This is because students are encouraged to speak in their home languages and thus maintain and nurture their knowledge of their mother tongue. The school’s motto is “multilingual permissiveness” because the learning itself seems to matter more than the language in which it is expressed.

Observing other lessons also provided us with interesting experiences and reflections. We participated in English, Mathematics, Computer Science, Biology, Household Economics, and PE classes. Both Greek and foreign students participated in these classes together. Above all, these lessons showed the importance of the role of the teacher in a multicultural class and the strategies employed for teaching students. Here, similarly to any other country, there appears the necessity to adjust the material to the abilities of all the students. It brings considerable difficulties in conducting lessons so that all pupils acquire knowledge equally effectively. It even appears that up to a certain point this goal is impossible to achieve, and concessions must be made.

The classroom observations also highlighted the key role of teachers’ subject knowledge. For example, in an English lesson, the teacher could build on the mastery of both foreign and Greek children. As a result, she taught the lesson in English, occasionally translating some phrases into Greek. In the biology lesson, YouTube videos helped in introducing the world of vertebrates and invertebrates. However, the language level of these videos was far too high, and proper use of the videos might be to first introduce key terminology and then watch the video. In Mathematics lessons, the universal language of calculations and notation of fractions, further illustrated graphically, was an ally. In the PE class, students danced while learning about Greek cultural heritage and music. In the Home Economics class, the teacher used pantomime, gestures, and facial expressions to make students aware of the differences between verbal and nonverbal communication. On the board, he summarized the collected findings in the form of a mind map.

It was clear from the observations that the teachers devote a lot of time, work and heart to prepare relevant activities. The students were also eager to cooperate with the teachers. The rapport between them was very good. However, it could be seen that teachers conduct lessons intuitively, and the way they adapt materials and teaching methods are not always effective. For example, in one lesson the class was divided into groups, but the groups did not work together but competed for points. In another subject, newly introduced terminology was not always presented in Greek, and some students did not have the opportunity to make sure they understood the concepts (e.g., the numerator and denominator in Mathematics, vertebrates and invertebrates in Biology). Sometimes teachers used too many different presentation techniques, resulting in the cognitive overload that amounted to the message that “the better is the enemy of the good” or “what’s too much is not healthy,” especially in the case of graphic materials and videos.

Additionally, the beginning of the school year meant that students did not yet have their textbooks and did not always have notebooks. The organization of the school could also be discussed in terms of methods to support student interaction and even the learning of Greek as a second language itself. Some changes would not require a lot of work or money. For example, rearranging the desks in classrooms and seating foreign students at desks closer to the teacher/ blackboard/ Greek colleague could significantly help these students not only in their learning but also contribute to their faster integration. However, Greek teachers are aware of their methodological and organizational shortcomings and hope that the MaMLiSE project will help them to adapt their ways of working to the needs of their students, taking into account the specificities of working in a multicultural school.

One of the biggest problems for students with migration backgrounds and their teachers is the motivation, or rather the lack of it, to learn Greek. Some students do not intend to stay permanently in Greece and plan to settle in another European country (e.g., Germany). However, they need at least a minimal knowledge of the official language to continue their studies while waiting for relocation. This conclusion could be drawn not only from the meeting with the teachers of the 2nd Junior High School of Ioannina but also from the discussions with the parents of the immigrant children. Thanks to the kindness of the host school, the project partners had the opportunity to take part in a meeting with them. Accompanied by community interpreters (in Farsi and Arabic), the parents shared with the MaMLiSE project partners their generally positive impressions of the cooperation with the school as well as the worries of everyday life in exile. The problems reported related more to the provision of learning materials and travel to the school than to dissatisfaction with their children’s academic performance. The regional coordinator of the Ministry of Education for foreign children also took part in the meeting. Her tasks include, in particular, helping children to find a suitable school and the general supervision of the educational process of non-Greek-speaking children. In her speech, she stressed the importance of sending the child to school in the place of current residence. She urged the assembled parents to tell others in their community to send their children to school no matter what country they associate their future with. She stressed the importance of continuity of learning, acquiring basic knowledge in Mathematics, History, Biology, Geography and other subjects. Children who attend school in Greece will receive appropriate certificates which, in the case of relocation, will enable them to continue their education in the destination country. She conveyed an important message, which became the informal motto of our project: School matters.

dr Izabela Czerniejewska, prof. dr hab. Anna Szczepaniak-Kozak